Our latest study just came out (Jeffares et al., Nature Comm 2017). In it, we carefully catalogued high-confidence structural variants among all known strains of the fission yeast population, and assessed their impact on spore viability, winemaking and other traits. This post gives a summary and the story behind the paper.

Structural variants (SVs) measure genetic variation beyond single nucleotide changes …

Next generation sequencing is enabling the study of genomic diversity on unprecedented levels. While most of this research has focused on single base pair differences (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs), larger genomic differences (called structural variations, SVs) can also have an impact on the evolution of an organism, on traits and on diseases. SVs are usually loosely defined as events that are at least 50 base pair long. They are often classified in five subtypes: deletions, duplications, new sequence insertions, inversions and translocations.

Over the recent years the impact of SVs has been characterized in many organisms. For example, SVs play a role in cancer, when duplications often lead to multiple copies of important oncogenes. Furthermore, SVs are known to play a role in other human disorders such as autism, obesity, etc.

… but calling structural variants remains challenging

In principle, identifying SVs seems trivial: just map paired-end reads to a reference genome, look for any abnormally spaced pairs or split reads (i.e. reads with parts mapping to different regions), and—boom—structural variants!

In practice, things are much harder. This is partly due to the frustrating tendency for SVs occur in or near repetitive regions where short read sequencing struggles to disambiguate the reads. Or in highly variable regions of genome such as the chromosome ends, which tend to be the tinkering workshop of the genome.

As a result, a large proportion of SVs—typically at least 30-40%—remain undetected. As for false discovery rates (proportion of wrongly inferred SVs), they are mostly not well known because validating SVs on real data is very laborious.

Fission yeast: a compelling model to study structural variants

Studying structural variants in Schizosaccharomyces pombe is especially suited because:

-

The genome is small, well-annotated and simple (few repeats, haploid).

-

We had 40x or more coverage over 161 genomes covering the worldwide known population of S. pombe.

-

We had more than 220 accurate trait measurements for these strains at hand. Since the traits are measured under strictly controlled conditions, they contain little (if any) environmental variance—in stark contrast to human traits.

SURVIVOR makes the most out of (imperfect) SV callers

To infer accurate SVs calls, we introduced SURVIVOR, a consensus method to reduce the false discovery rate, while maintaining high sensitivity. Using simulated data, we observed that consensus calls obtained from two to three different SV callers could recover most SV while keeping the false-discovery rate in check. For example, SURIVOR performed second best with a 70% sensitivity (best was Delly: 75%), while the false discovery rate was significantly reduced to 1% (Delly: 13%) (but remember these figures are based on simulation; performance on real data is likely worse.) Furthermore, we equipped SURVIVOR with different methods to simulate data sets and evaluate callers; merge data from different samples; compute bad map ability regions (BED file) over the different regions, etc. SURVIVOR is written in C++ so it’s fast enough to run on large genomes as well. Since then, we are running it on multiple human data sets, which takes only a few minutes on a laptop. SURVIVOR is available on GitHub.

SVs: now you see me, now you don’t

We applied SURVIVOR to our 161 genomic data sets, and then manually vetted all our calls to obtain a trustworthy set of SVs. We then discovered something suspicious. Some groups of strains that were very closely related (essentially clonal, differing by <150 SNPs) had different numbers of duplications, or different numbers of copies in duplications (1x, 2x, even 6x). This observation was also validated with lab experiments.

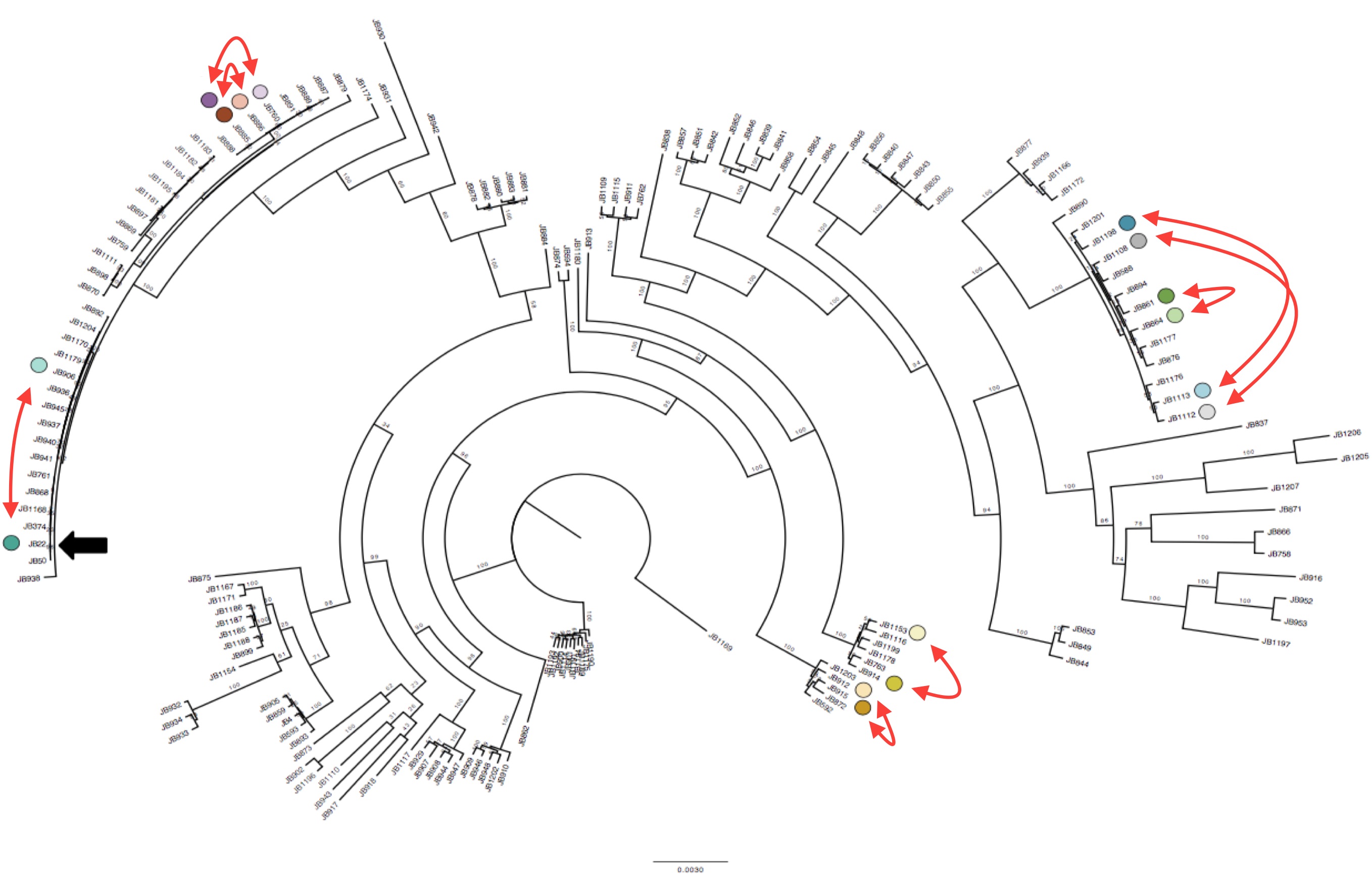

Interestingly we identified 15 duplications that were shared between the more diverse non-clonal strains (so these must have been shared during evolution) but could not be explained by the tree inferred from SNPs (Figure 1). To confirm this we compared the local phylogeny of SNPs in 20kb windows up and downstream of the duplications with the variance in copy numbers. Oddly the copy number variance was not highly correlated with the SNP tree. This lead to the conclusion that some SVs are transient and thus are gained or lost faster than SNPs.

Duplications happen within near-clonal populations Phylogenetic tree of the strains reconstructed from SNPs data, with eight pairs of very close strains that nonetheless show structural variation. Click to enlarge.

Though this transience came as a surprise, there is actually supporting evidence from laboratory experiments carried out by Tony Carr back in 1989 that duplications can occur frequently in laboratory-reared S. pombe, and can revert. (Carr et al. 1989). The high turnover raises the possibility that SVs could be an important source for environmental adaptation.

SVs affect spore viability and are associated with several traits

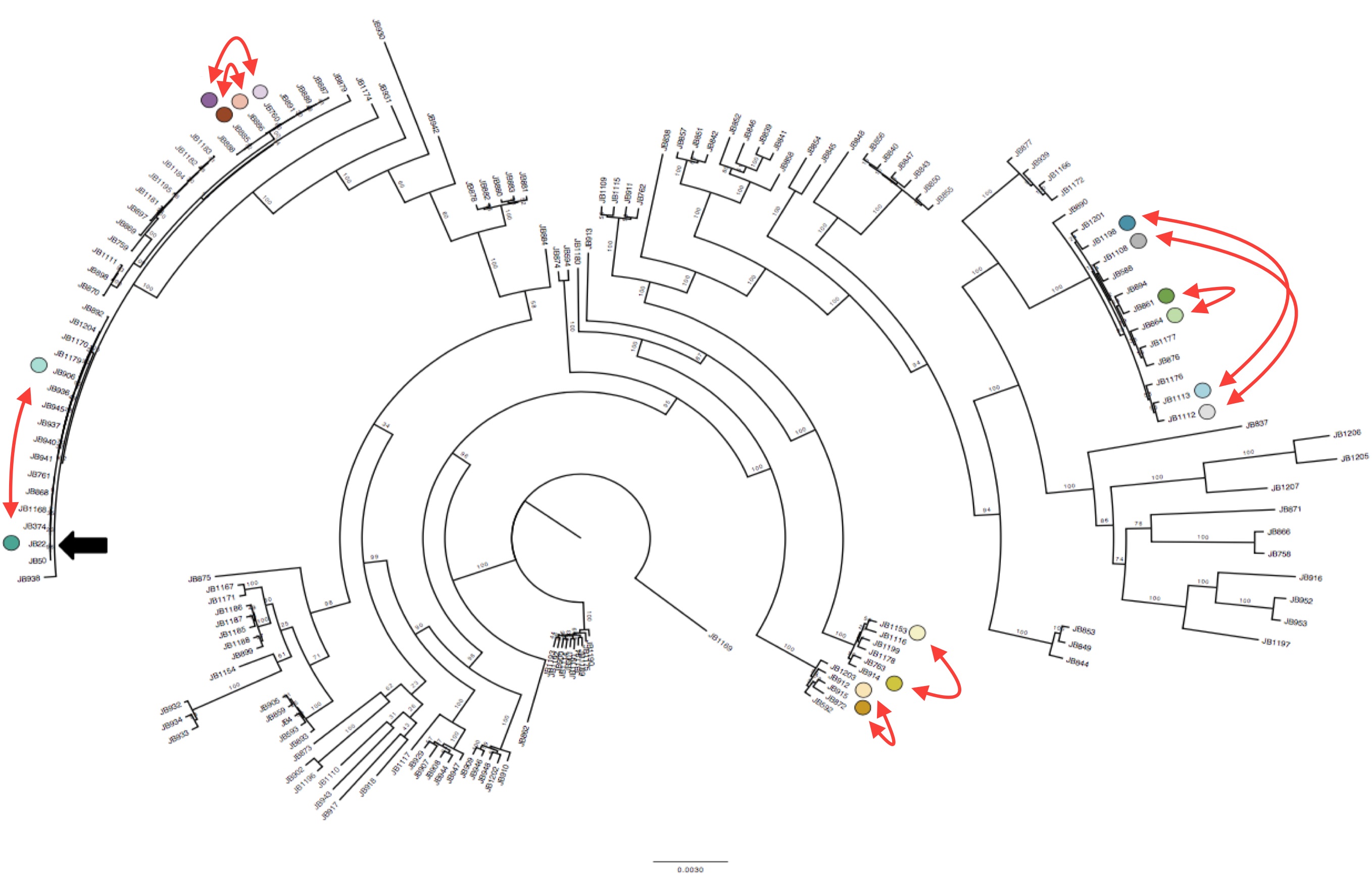

We then investigated the phenotypic impact of these SVs. We used the 220 trait measurements from previous publications. We observed an inverse correlation between rearrangement distance and spore viability, confirming reports in other species that SVs can contribute to reproductive isolation. We also found a link between copy number variation and two traits relevant to wine making (malic acid accumulation and glucose+fructose ultilisation) (Benito et al. PLOS ONE 2016).

Structural variants, reproductive isolation, and wine. A) Making crosses between fission yeast strains often results in low offspring survival. The theory is that rearrangements (inversions and translocations) cause errors during meiosis, so we might expect them to affect offspring viability. If we compare offspring viability from crosses with the number of rearrangements that the parents differ by, there is a correlation, and a ‘forbidden triangle’ in the top right of the plot (it seem impossible to produce high viability spores when parents have many unshared rearrangements). B) SVs also affect traits. For > 200 traits (vertical bars) we used [LDAK](http://dougspeed.com/ldak/) to estimate the proportion of the narrow sense heritability that was caused by copy number variants (red), rearrangements (black) and SNPs (grey). Some traits are very strongly affected by copy number variants, such as the wine-making traits (wine-colored bars along the x-axis). C) Fission yeast wine tasting at UCL–how much of the taste is due structural variants? (Jürg Bähler at right).

We used the estimation of narrow sense heritability from Doug Speed’s LDAK program. Narrow sense heritability estimates how much of a difference in a trait between individuals can be explained by adding up all the tiny effects of the genomic differences (in our case SNPs; deletions and duplications; inversions and translocations and all combined). Overall, we found the heritability was better explained when combining the SNP data as well as the SVs data. In 45 traits SVs explained 25% or more of the trait variability. Five traits that were explained by over 90% heritability using SNPs and SVs came from different growth conditions in liquid medium. This may highlight again the influence of environmental conditions on the genomic structure. For 74 traits (~30% of those we analyzed) SVs explain more of the trait than the SNPs. These high SV-affected traits include malic acid, acetic acid and glucose/fructose contents of wine, key components of taste.

A collaborative effort

On a personal note, the paper concludes a wonderful team effort over two and a half years.

The project started as a summer project for Clemency Jolly, who had then just completed her 3rd undergraduate year at UCL, in the Dessimoz and Bähler labs. Dan Jeffares and the rest of the Bähler lab had just published their 161 fission yeast genomes, with an in-depth analysis of the association between SNPs and quantitative traits (Jeffares et al., Nature Genetics 2015). Studying SVs was the logical next step, but given the challenging nature of reliable SV calling, we also recruited to the team Fritz Sedlazeck, collaborator and expert in tool development for NGS data analysis then based in Mike Schatz’s lab at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

At the end of the summer, it was clear that we were onto something, but there was still a lot be done. Clemency turned the work into her Master’s project, with Dan and Fritz redoubling their efforts until Clemency graduation in summer 2015. It took another year of intense work lead by Dan and Fritz to verify the calls, perform the GWAS and heritability analyses, and publish the work. Since then, Clemency has started her PhD at the Crick Institute, Fritz has moved to John Hopkins University, and Dan has started his own lab at the University of York.

References:

Jeffares, D., Jolly, C., Hoti, M., Speed, D., Shaw, L., Rallis, C., Balloux, F., Dessimoz, C., Bähler, J., & Sedlazeck, F. (2017). Transient structural variations have strong effects on quantitative traits and reproductive isolation in fission yeast Nature Communications, 8 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms14061

Carr AM, MacNeill SA, Hayles J, & Nurse P (1989). Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of mutant alleles of the fission yeast cdc2 protein kinase gene: implications for cdc2+ protein structure and function. Molecular & general genetics : MGG, 218 (1), 41-9 PMID: 2674650

Jeffares, D., Rallis, C., Rieux, A., Speed, D., Převorovský, M., Mourier, T., Marsellach, F., Iqbal, Z., Lau, W., Cheng, T., Pracana, R., Mülleder, M., Lawson, J., Chessel, A., Bala, S., Hellenthal, G., O’Fallon, B., Keane, T., Simpson, J., Bischof, L., Tomiczek, B., Bitton, D., Sideri, T., Codlin, S., Hellberg, J., van Trigt, L., Jeffery, L., Li, J., Atkinson, S., Thodberg, M., Febrer, M., McLay, K., Drou, N., Brown, W., Hayles, J., Salas, R., Ralser, M., Maniatis, N., Balding, D., Balloux, F., Durbin, R., & Bähler, J. (2015). The genomic and phenotypic diversity of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Nature Genetics, 47 (3), 235-241 DOI: 10.1038/ng.3215

Benito, A., Jeffares, D., Palomero, F., Calderón, F., Bai, F., Bähler, J., & Benito, S. (2016). Selected Schizosaccharomyces pombe Strains Have Characteristics That Are Beneficial for Winemaking PLOS ONE, 11 (3) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151102